How democracy vouchers could change local politics in LA and beyond

April 14, 2024

Welcome to the sixth issue of Report Forward by journalist Alissa Walker.

THE BIG REPORT

Democracy vouchers are like a ticket to voter engagement. Photo by Tom Latkowski

Are you a Los Angeles city resident who donated to a candidate in the March primary? Maybe, by poking around online, you found out about the city’s program which matched your donation 6:1 (but only if your candidate had already raised enough money to access the program itself). You may be surprised to learn that, of the $7.65 million total donated in the city’s March primary, just $1.7 million came from people who live in LA City like you, with those matching funds kicking in another $1.9 million. The biggest chunk of donations came from people outside of LA City: $2.9 million, or 38.4 percent. And another $1 million was donated by non-individuals such as corporations, unions, partisan nonprofits, and political action committees (PACs) inside and outside of the city. Yes, despite the city matching so many LA resident donations, about half of the money in LA’s 2024 primary election (47.5 percent) still came from groups and people who aren’t even in LA. Is this really how it’s supposed to work?

Now imagine it’s the 2028 primary. You receive four coupons with your ballot, each valued at $25 each, which can be allocated to the fundraising campaigns of the candidates of your choice. Contributing to an LA candidate is as easy as voting using a mail-in ballot — you can also do it online — but instead of money coming out of your pocket, these donations would be paid for by the city itself. These are called democracy vouchers, and even though the whole thing sounds too good to be true, this system is currently in place in Seattle, coming soon to Oakland, and, thanks to a dedicated coalition of campaign finance reform groups, closer to reality in LA than you might think. “We've seen them diversify the pool of donors,” says Tom Latkowski, a co-leader of Los Angeles for Democracy Vouchers and the author of Democracy Vouchers: How Bringing Money into Politics Can Drive Money Out of Politics. “We've seen them expand who can run for office. And we've seen them boost political engagement. So that's why we're working so hard to pass this.”

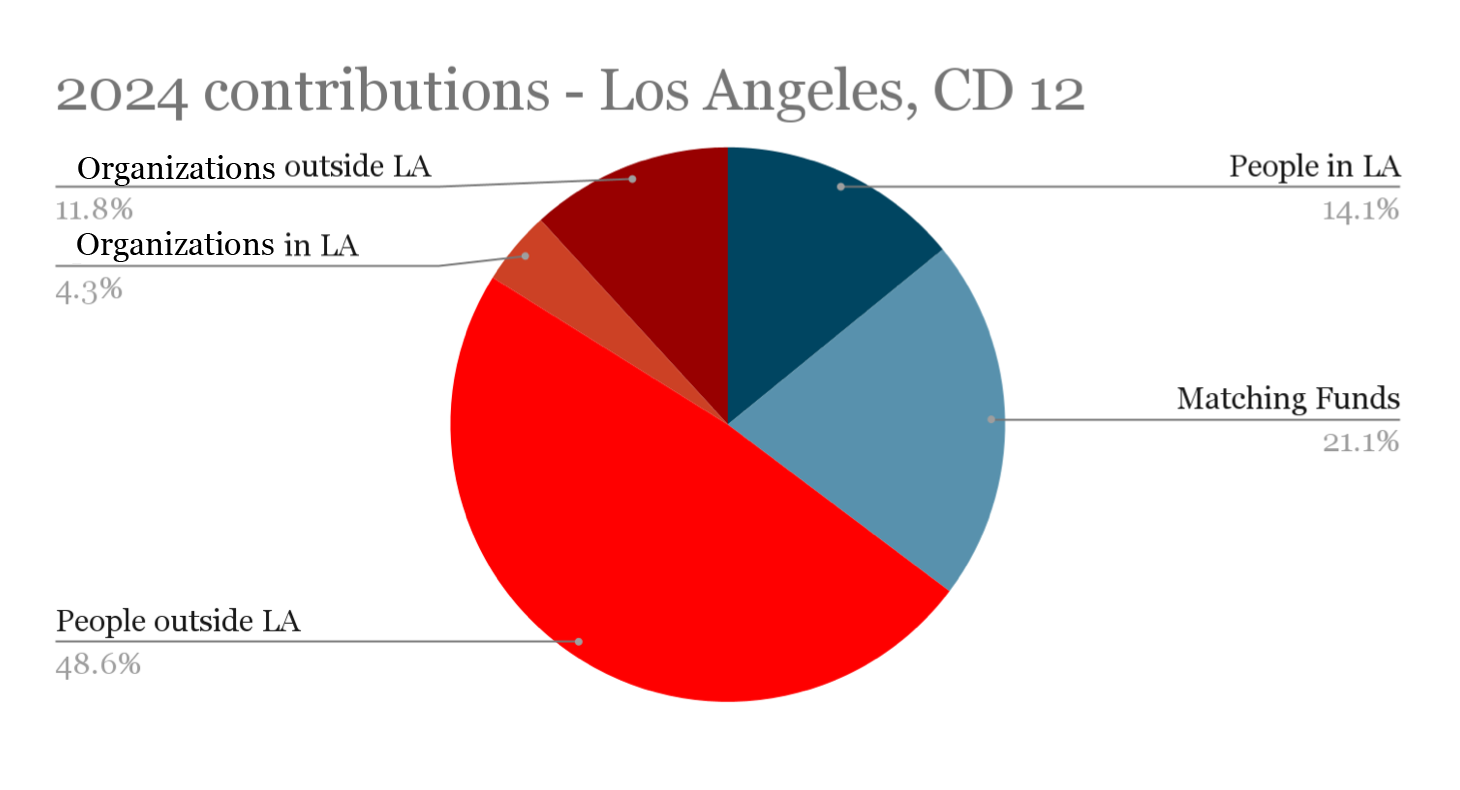

A majority of LA’s 2024 political contributions came from people outside LA and non-individuals, including organizations such as corporations, business associations, unions, 501(c)(4) nonprofits, and political action committees (PACs)

In the Council District 12 race, where former Republican John Lee won in the election in the primary with 62 percent of the vote, 60.4 percent of all contributions came from outside of LA. Created by Tom Latkowski of Los Angeles for Democracy Vouchers, with additional edits by LA Forward Institute.

Last June, LA’s City Council adopted a motion introduced by Councilmembers Nithya Raman, Hugo Soto-Martinez, and Marqueece Harris-Dawson that will soon deliver recommendations for how the city could implement its own democracy voucher program like Seattle. And last September, Latkowski and his Los Angeles for Democracy Vouchers co-leader Mike Draskovic published the most comprehensive local report on the topic yet: “Exploring Reform: A Compendium of Research, Reports, and Modeling of Democracy Vouchers in Los Angeles.” Crunching two decades of campaign finance data, the need for reform is clear: Angelenos who donate to city campaigns tend to overwhelmingly come from the richest and whitest neighborhoods. That means many candidates spend time and energy courting those likely donors instead of engaging more with their own potential constituents, says Draskovic, who is also co-founder of the Democracy Policy Network. “They're listening to people from wealthier backgrounds and their priorities, and they're not getting a holistic sense of what Angelenos want to see in their public officials.”

A decade ago, Seattle was in the same situation. Before the city’s implementation of democracy vouchers, one of the best predictors of whether or not someone was going to be a donor was whether or not their house had a view of the water. Since democracy vouchers were first rolled out in 2017, astonishing data shows a remarkable shift in campaign contributions, with the demographics of donors aligning more closely with the demographics of voters across age, race, and income. These figures also have become more representative with every subsequent election. Additionally, the amount of campaign money from outside the city has dropped by 36 percent. And because public financing lowered the bar for entry, the average number of people running in Seattle City Council races has increased after democracy vouchers were implemented.

Democracy vouchers might also be more effective than other efforts to increase participation in elections, like universal mail-in voting or synching up local races with federal races. Vouchers are sent out regardless of voter registration status — in Seattle, vouchers go to all citizens and permanent residents over 18— and there is strong evidence that they really do move the needle on turnout, says Latkowski. “In Seattle, we've seen data that when previous non-voters use a democracy voucher, they then become six to 10 times more likely to vote.”

In Seattle, the number of individuals participating in the campaign finance system has grown over 500 percent since democracy vouchers were introduced in 2017. Chart by Seattle Ethics and Elections Commission

To their credit, LA’s elected officials have already taken a few key steps to try to level the campaign-finance playing field, including the 2019 amendment of the existing matching funds program to “supermatch” donations 6:1. (Although only thanks to pressure from reform advocates and the need to save face amid a string of scandals.) In this year’s elections, the maximum eligible donation of $129 for a city council race, when matched, can become $903 — notable because that will make the contribution of an LA city donor equal to the $900 maximum donation allowed by any individual or entity inside or outside the city. Those 2019 amendments also reduced other thresholds for candidates, including the amount of donations they must raise in order to qualify for matching funds. Those thresholds were not lowered enough for many advocates’ taste, who argue it’s still too hard for candidates — including some who did not qualify in March’s primary — to unlock the benefits.

But while matching funds are better than nothing, anything that requires disposable income to participate still creates a barrier, Latkowski says. “If I'm someone with $0 of disposable income, and my donation gets multiplied by six, well… six times $0 is still $0. And so there's just a lot of people that are left out.”

It’s easy to see why voters might get more energized about a candidate when they have what feels like Monopoly money to donate. But because they incentivize direct interaction with voters, democracy vouchers can also dramatically change the way candidates campaign. Vouchers can only be redeemed from potential LA city constituents — candidates can physically collect them when they canvas a neighborhood or table at community events — which rewards in-person engagement and shifts attention away from wealthy outside donors. This has also been the way LA’s progressive campaigns have been winning elections lately. In this year’s March primary, a focus on door-knocking for Ysabel Jurado (Council District 14) and Jillian Burgos (Council District 2) landed the two grassroots candidates in their respective runoffs. Jurado and Burgos poured donations back into canvassing — and funding even more time spent interfacing with voters.

While democracy vouchers don’t eliminate the power of wealthy donors — or wealthy candidates like Rick Caruso, who spent $100 million of his own money to lose the 2022 mayoral race —Latkowski and Draskovic argue more public financing can start to chip away at their influence.As cities and states move towards more robust publicly financed models, they can place additional conditions on candidates who accept that funding. LA’s democracy voucher program could be custom-designed to build upon its matching funds system or implement a full public financing model, where candidates get a lump-sum grant to pay for their entire campaign with public money. (In Arizona and Maine, these voluntary “clean election” programs are so popular that state candidates often opt to not accept private money at all.) Modeling by Latkowski and Draskovic as well as the California Clean Money Campaign shows this hybrid model could be implemented citywide in LA for an estimated $12 to $20 million per year — a corruption mitigation tool that’s just 0.15 percent of the city’s budget.

In the 2022 election, the average donation from LA’s majority white ZIP codes was 2.28 times the average donation from majority people of color ZIP codes. Map from Exploring Reform: A Compendium of Research, Reports, and Modeling of Democracy Vouchers in Los Angeles

Ideally, LA’s City Council would place a democracy voucher proposal on the November 2024 ballot as part of a package of good government reforms, including independent redistricting and council expansion (and, hopefully, much-needed ethics reforms). But it’s also possible that a decision like this could be put forth by a to-be-created charter commission, another option recently advanced by the council’s Ad Hoc Governance Reform committee. Plan C would force advocates to gather enough signatures to put democracy vouchers on the ballot as a citizen-sponsored measure, which would be arduous and expensive for an ethically challenged city like LA that doesn’t have time or money to waste.

Cleaning up the money in LA politics doesn’t end with a voucher system, of course. The holy grail of campaign finance reform is overturning the 2010 Supreme Court ruling Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, which removed spending caps for the secretive independent expenditure committees that currently dump millions of outside dollars into LA’s elections. (This year, $1.35 million in independent expenditures were spent in an attempt to beat Raman, who still won outright in the primary.) But until that happens, democracy vouchers are something that the city of LA could easily implement to make its elections more representative and more fair — and to Latkowski and Draskovic, the evidence from Seattle is irrefutable. “To see that many new voices come into the campaign finance system, that’s meaningful,” says Draskovic. “But to see the diversification of the donor pool and the candidate pool, and just the sheer number of people participating in that voting who otherwise weren't voting before — that’s just remarkable.”

Want to learn more about what democracy vouchers could do for LA? Watch this video briefing held by LA Democracy Vouchers featuring local experts, reform advocates, and elected officials.

PROGRESS REPORT

Just 12 months after Measure ULA began collecting a transfer tax on LA city real estate transactions over $5 million to fund affordable housing efforts, 4,652 LA households have received emergency rental assistance from this fund. That’s an estimated 11,000 Angelenos who have stayed housed since voters approved the initiative in 2022, in addition to nearly 5,000 renters who received legal representation or advice through ULA programs. And, according to “Measuring LA’s Mansion Tax: An Evaluation of Measure ULA’s First Year” published by researchers at Occidental College, USC, and UCLA this month, not only has the $215 million generated by ULA to date become the city’s single-largest source of revenue for affordable housing and homelessness prevention, it’s more than twice the amount that the federal government gave LA for similar programs in the past year.

ULA supporters gather at the 100 percent affordable Santa Monica Vermont Apartments. Photo by United to House LA

As the report notes, ULA’s revenue has also trended upwards despite an overall cooling of the local real estate market attributed to many factors outside of LA’s control, like sky-high interest rates, rising construction costs, and inflation. But ULA’s money is also helping affordable housing developers navigate those same financial challenges. Earlier this month, ULA supporters rallied in the courtyard of the Santa Monica Vermont Apartments, a 187-unit affordable housing complex atop the B line Metro station, which ran into financing issues when its construction interest rate was raised from 2.7 to 7.5 percent, jeopardizing its completion. Now, $2.5 million of ULA funds will go towards the Santa Monica Vermont Apartments — one of nine projects set to be expedited through a new proposal to use ULA money to close affordable housing funding gaps. ULA’s support was critical, according to Tak Suzuki, Director of Community Development at Little Tokyo Service Center. “Without Measure ULA funding we would be unable to get this project finished.”

LOCAL REPORT

14 percent of LA’s rental housing has three bedrooms or more, creating widespread overcrowding in a city of renters where one-third of families have four people or more. (In comparison, 70 percent of LA’s homes owned by residents have three bedrooms or more.) But social housing could help address the shortage.

$30 million would open and staff existing restrooms at Metro rail stations across the region, providing riders unprecedented comfort and safety while saving cleaning and maintenance dollars. It’s just one way that Metro’s $134.5 million plan to create an in-house police force would be better spent, according to ACT-LA’s new campaign.

16 to 26 percent of a family’s income is spent on child care per child in LA, on average, while the precarious financial state of local child care facilities means many child care workers are severely underpaid. Last month, the City of LA’s Community Investment for Families Department report and recommendations were approved for a new citywide strategic approach, the Child Care Equity Initiative.

300 emergency calls have been diverted from LAPD to new unarmed response teams since March 12, Councilmember Monica Rodriguez announced last week. Years in the making, the new Unarmed Model of Crisis Response (UMCR) pilot program finally launched, with two two-person service teams operating in three service areas around the clock.

$4.3 billion in stormwater investments must be made by 2040 to prevent devastating flooding and deadly heat, according to the Los Angeles County Climate Cost Study. Of the total estimated $12.5 billion in climate adaptation costs needed, the Center for Climate Integrity study recommends over one-third be devoted to stormwater interventions like bioswales and permeable pavement.

STATE REPORT

EXTREME MEASURES: A new database by SPUR tracks the 208 land-use ballot measures passed in the state since the1970s and how they’ve impacted housing supply. LA County leads with 25 measures that have restricted housing production.

NOBODY HOME: Nine California agencies have spent billions on 30 homelessness programs, but the state hasn’t tracked the effectiveness of this spending since 2021, says a new California State Auditor report.

EMISSIONS OMISSIONS: California is not on track to meet its climate goals and will need to triple its efforts to hit its 2030 targets, says Next 10’s California Green Innovation Index. The largest increase is in the transportation sector, where emissions went up 7.4 percent.

NOT GOING WELL: Efforts to make oil companies pay to cap and clean up over 2 million orphan wells aren’t working and California might be on the hook for billions in remediation costs, according to a Capital & Main and ProPublica investigation.

FIELD REPORT

California Community Foundation CEO Miguel Santana in conversation with Investing in Place executive director Jessica Meaney. Photo by Investing in Place

Over 90 Angelenos joined Investing in Place for “The Public Way: Making Infrastructure Work for People,” the organization’s winter convening highlighting the need for a citywide capital infrastructure plan, a multi-year strategy to fund and implement public works improvements. Speakers included LA City Councilmember and chair of the Budget and Finance Committee Bob Blumenfield, Destination Crenshaw CEO Jason Foster, and California Community Foundation CEO Miguel Santana, who served as Chief Administrative Officer at the City of LA during the previous budgetary crisis and said not having a capital infrastructure plan in place made his job harder. “A plan helps you define what’s most important,” said Santana. “Before we get to the distribution of resources or prioritization of which communities get what first, we need a shared vision of what kind of community we want to have, from the perspective of the community.”

Coming up next…

Social Justice Partners LA is holding its legendary Fast Pitch event back in-person again at the California Endowment on Tuesday, April 23. LA Forward Institute’s own Godfrey Plata will be one of the nonprofit leaders sharing their visions for LA! Tickets available here.

REPORT IN

Hi, Alissa Walker here — I’ll be compiling Report Forward every month. Please send reports, studies, white papers, and big policy wins to me at reports@laf.institute — and forward this to someone working to make LA a better place.

Want to make sure to get these issues every month? Sign up for our email list below!